Project Description

There are many reasons to learn a foreign language. The ability to communicate in multiple languages can lead to both an increased understanding of cultural differences throughout our world, as well as an increased ability to thrive in the global economy.

The Rensselaer Immersive Language Learning Environment (ILLE) is at the forefront of advanced research in cyber-enabled classrooms for language learning. It leverages cognitive and mixed reality technology to immerse students in various cultures, encourage them to practice daily tasks, and provide help from intelligent agents. ILLE utilizes established language pedagogy and advanced teaching methods to enable intelligent agents that language learners can listen to and mimic within a simulated cultural context as part of their learning process. The unprecedented nature of the ILLE allows for researchers to explore all of the possibilities of using artificial intelligence in the classroom.

Mission

Cognitive computing systems are increasingly prevalent in our society. The ways in which we engage information in our daily lives are becoming ever more immersive. The paradigm of human-computer interaction will soon shift towards partnerships between human beings and intelligent machines through human-scale and immersive experiences.

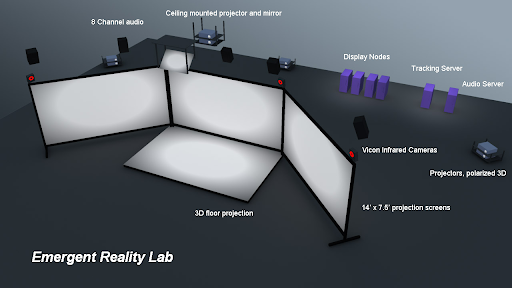

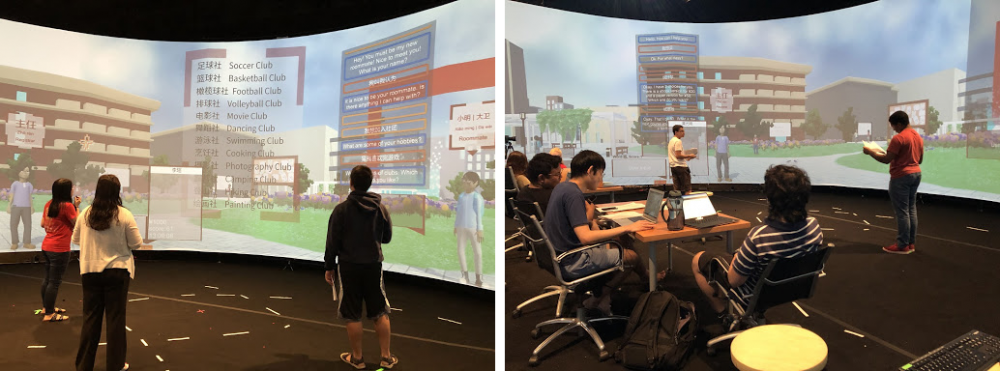

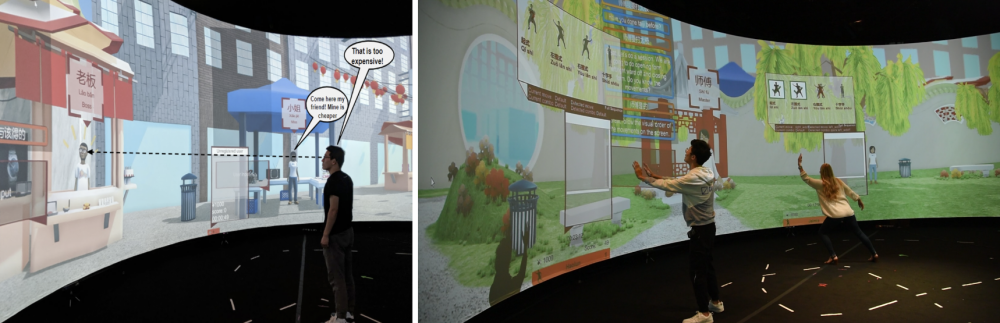

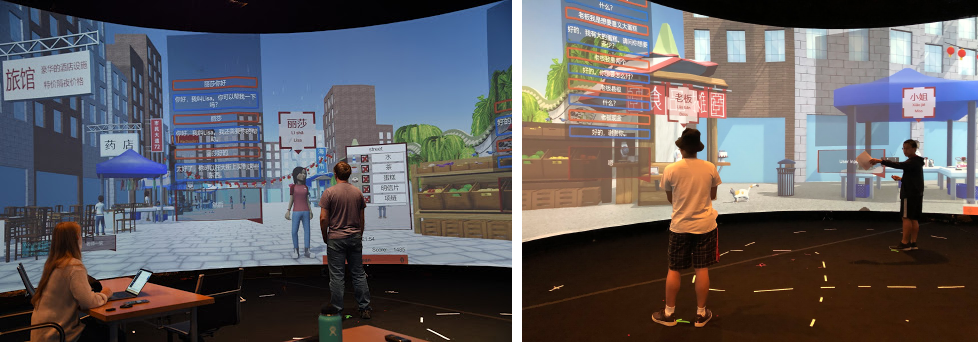

The ILLE works to integrate three key components to create a new type of learning environment: game, immersion, and interaction with cognitive agents. In addition to working with X Reality (XR), the ILLE is investigating human-scale environments where students can physically walk around the Cognitive and Immersive Systems Architecture (CIRA) without having to wear specialized equipment. These affordances present a unique approach which has the potential to greatly benefit the language and cultural learning the user is able to gain from the experience.

Immersed in an engaging teaching medium, students are better motivated to absorb language. Playing an educational game is more engaging than sitting through a lecture and trying to learn from rote memorization. In a similar vein, the immersive aspects of games help students feel as though they are practicing their language skills in authentic, real-life situations, while at the same time freeing them from the stressors that come from speaking with a native speaker. Since the cognitive agents are enabled by AI systems for their language processing, students are able to converse with partners who have infinite patience to help them through their learning experiences.

Vision

The future of language practice lies in multimodal immersive systems. Being able to listen to others speak, as well as receiving critique on pronunciation, is imperative to master a language. For a tone-based language like Mandarin Chinese, where proper intonation dramatically affects the meaning of words, immersion is critical for improved pronunciation.

Current solutions for immersive language practice, however, are often inaccessible. Studying abroad is expensive, and most educational programs do not have the resources to provide conversational partners to work with students one-on-one — the same immersive, multimodal speech practice that travel offers. While most language learning programs are also eager to incorporate new technology, the options currently available make it challenging to find viable solutions. Many language learning services are conveniently offered online, yet they focus on the memorization of vocabulary rather than speech practice. As a result, they underperform when compared to immersive, multimodal applications with authentic spoken conversation opportunities.

The ILLE has established RPI as a leader in cyber-enabled language learning research through in-classroom user studies in Mandarin instruction starting during the Summer of 2017. While the project in its current capacity is focused around multimodal input, speech, and language, there are future plans to involve a broader physically immersive experience for a large number of participants. Students will one day be able to walk through different environments and engage with a society of agents that provide more rich and intimate interactions to refine their language skills and expose them to nuances.

History

In the spring of 2013, professors Lee Sheldon, Ben Chang, and Mei Si collaborated with Jianling Yue and Yalun Zhou to create the Mandarin Project: a hybrid of immersive classroom experiences and virtual reality adventures designed to engage students as they master Chinese.

Lee Sheldon, a professional game writer, designer, and current professor at WPI, is the author of the bestselling book, The Multiplayer Classroom: Designing Coursework as a Game (2011); his book, Character Development and Storytelling for Games (Second Edition, 2013), is the standard text in the gaming industry.

Ben Chang is an electronic artist and director of the Games and Simulation Arts and Sciences program at Rensselaer. His work explores the intersections of virtual environments and experimental gaming bringing out the chaotic, human qualities in technological systems.

Mei Si has an expertise in artificial intelligence and its application in virtual and mixed realities. Her research concentrates on computer-aided interactive narratives, embodied conversational agents, and pervasive user interface, elements that make virtual environments more engaging and effective.

During their collaboration, the team adopted the philosophy that language is always situated in a culture and in a physical location — connected to a place and to people, not just an isolated thing. So, to experience language in that way, in a cultural and spatial context, is a valuable thing. With the additional elements of gameplay and narrative, there are heightened motivational, interest, and engagement levels with the learning.

In 2017, the cognitive aspects of the Mandarin Project were then further developed by the Cognitive and Immersive Systems Laboratory (CISL) into a virtual cultural immersion trip to China. At the time, CISL was a collaboration between IBM Research and RPI, and the Mandarin Project was one of the four use cases in the Lab. Early CISL goals for the Mandarin Project included combining the benefits of a cognitive, immersive technology to let students engage in a cultural environment, practice daily tasks, and obtain help from intelligent agents. The Mandarin Project was able to leverage cognitive technology to act as a personalized language tutor. This allowed students to listen to and repeat correct pronunciation and intonation while learning the language.

By 2020, the team had grown to bring on additional designers and writers who helped pivot the game to its current sci-fi XR form — 印迹:龙吟 (Bāndiǎn: Lóng yín / ENGRAM: Dragon’s Roar). The top level project has also been re-named to the Immersive Language Learning Environment (ILLE) as the institute looks to expand into a global approach that includes the many languages of our world.

Approach

Pedagogy

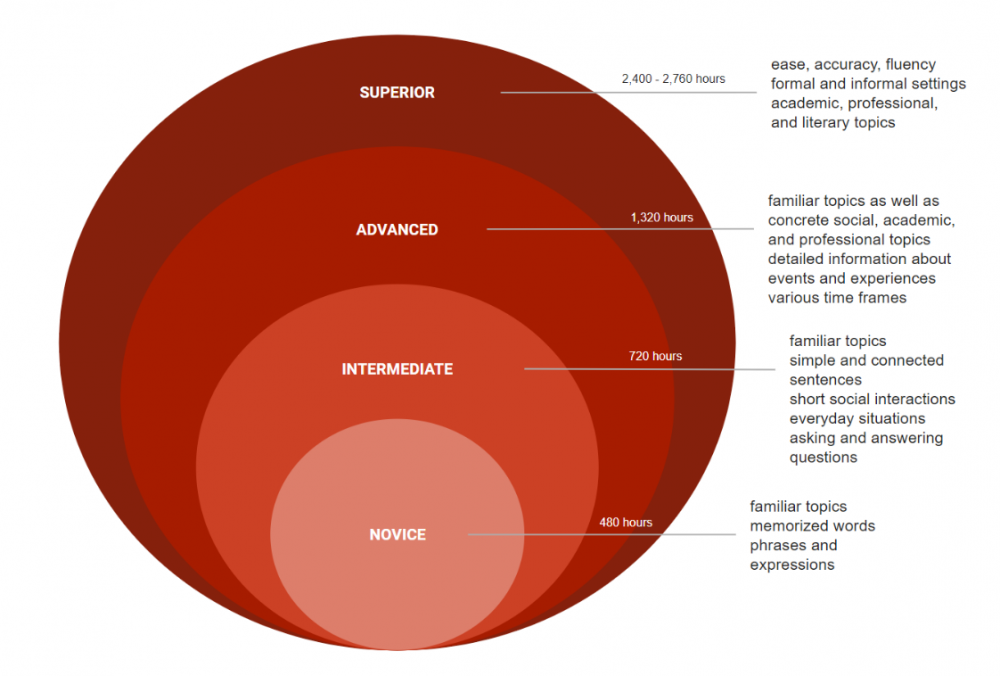

The Immersive Language Learning Environment (ILLE) project aims to increase access to language instruction in order to enable the rapid acquisition of foreign languages. Complementary to classroom learning, in the ILLE students are exposed to survival phrases, vocabulary words, multi-round dialogues, and cultural notes. These complex interactions are enabled by different experiences and technologies. Virtual worlds allow students to explore and complete sophisticated dialogues with multiple AI agents. Students can also explore panoramic images that are overlaid with vocabulary, conversational, and cultural interactions. The ILLE incorporates these diverse, complex interactions and experiences to support the attainment of the different proficiency levels outlined by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL).

An early prototype of the ILLE leverages speech-based dialogue for communication and information exchange in Mandarin Chinese between students and agents in an immersive environment. It utilizes task-based language learning to give students meaningful language practice in order to develop a sense of confidence and fluency in the language. Students engage in task-oriented group activities through communication and interpersonal social practices. Constant exposure with the ILLE may facilitate students to speak more naturally with faster language acquisition, since they are able to interact in real-life situations without needing to travel abroad.

The immersive learning environment aims to reduce the number of hours students require to learn how to speak on the same level as a native speaker. Rather than teaching the students basic vocabulary and having them rely on relevant outside media to teach natural speech structure, the ILLE allows for the students to learn language as one would if they were living in a foreign language–speaking community. The project takes a holistic perception of foreign language linguistics, vocabulary, and culture aiming to produce students who can speak with a proficient level of fluency and understanding.

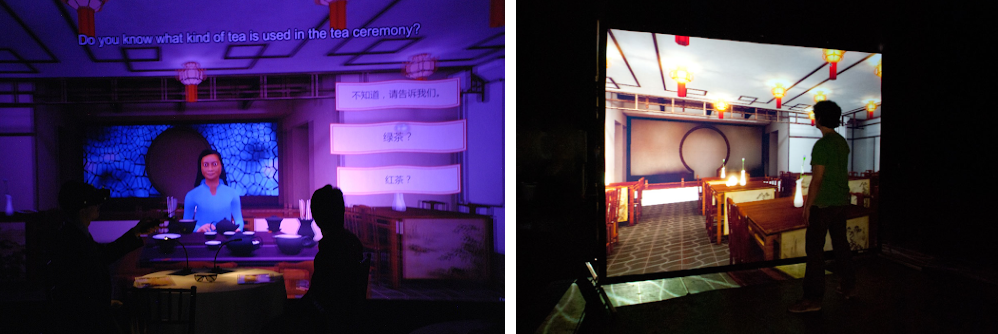

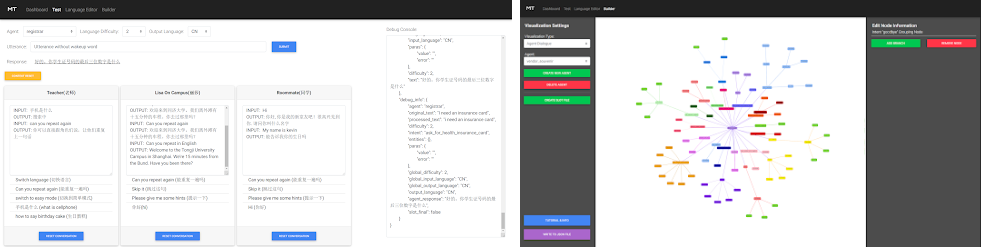

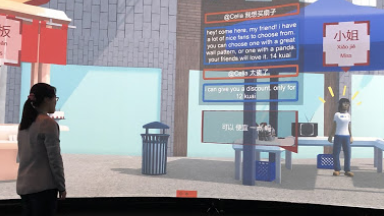

The current game, 印迹:龙吟 (Bāndiǎn: Lóng yín / ENGRAM: Dragon’s Roar), focuses on tasks like ordering from a restaurant entirely in Mandarin. Students navigate through different restaurant-oriented tasks, such as asking for a table, ordering from a friendly cognitive agent named Chongshan, and paying for their meal. The students taking part in this simulation have the option to ask any number of questions to the eternally patient Chongshan. In contrast with human partner conversations, virtual agents can reduce the social anxiety of mispronunciation in front of a native speaker. Along with providing vocabulary and pronunciation support, Chongshan also gives cultural information about the menu items to enrich the user’s experience.

Technology—how the situations room is used for the purpose of language learning

CIRA

In order to fully integrate the power of cognitive and immersive computing together for language teaching, the Cognitive and Immersive Systems Laboratory (CISL) set up an immersive classroom environment in EMPAC Studio 2 at RPI. Chinese, German, Spanish, and English speech recognition, conversation with natural language processing, multimodal interaction, narrative design, and more were enabled using cognitive computing technologies.

The ILLE is proud to be a research-based language learning environment. Researchers across multiple disciplines are working together to create a modern, multimodal learning environment that uses artificial intelligence to its advantage. This allows the project to be flexible and focus on several areas of development to find what is technologically useful. The researchers are currently working to use artificial intelligence to integrate speech and gesture recognition within the classroom to monitor student interaction and dialogue.

印迹:龙吟 (Bāndiǎn: Lóng yín / ENGRAM: Dragon’s Roar) Game

印迹:龙吟 (Bāndiǎn: Lóng yín / ENGRAM: Dragon’s Roar) is a Sci-Fi XR Educational Role-Playing Game (RPG) that teaches Mandarin Chinese within the Rensselaer Cognitive and Immersive Language Learning Environment (ILLE). As a player, you have just been hired to fill the position of a cognitive restoration technician at Engram Enterprises. Your first patient, 李崇山 (Lǐchóngshān / Li Chongshan), needs your help to rebuild his memories and cognitive functions with the assistance of his daughter 李若龙 (Lǐruòlóng / Li Ruolong). You soon find out the two of them are irreparably estranged, and slowly realize your treatment may be their last hope to make things right before he dies.

Educational perspective

ENGRAM: Dragon’s Roar leverages cognitive and XR technology to immerse college-level students in a sample of Chinese culture, practice daily tasks, and get help from intelligent agents. Results from early prototype user studies show a significant improvement in Chinese as foreign language (CFL) vocabulary, comprehension, and conversation skills after four one-hour learning sessions in the environment.

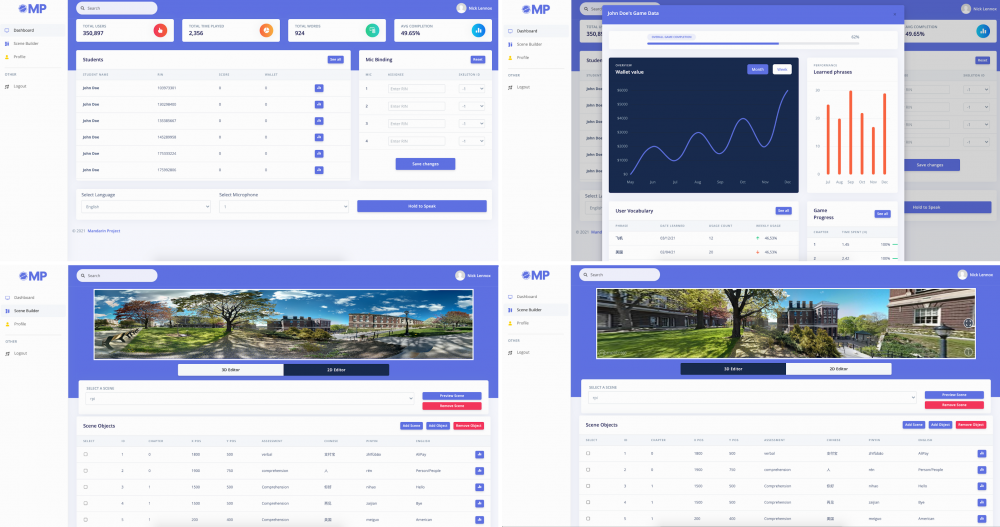

Core technologies

ENGRAM: Dragon’s Roar enables college-level students to dive into Li Chongshan’s mind using multimodal input — students point and say “印迹,我要去那里” (Bāndiǎn, wǒ yào qù nǎ lǐ / Engram, take us there) — to teleport through Chongshan’s memories and complete language learning activities. A personal profile keeps track of each student’s progress. Students are able to reflect on the information on their profile to self-direct their own learning, becoming inspired to level up and rack up scores as they successfully complete spoken dialogues with NPCs.

Multi-agent multi-modal negotiations module

Exposre to non-dyadic conversation also is a part of language learning as students must be aware of how to interact in groups in addition to individual interactions. A multi-modal multi-agent system that can infer which agent is being addressed (without the use of a wake-up word) and which agent should respond enables the aforementioned non-dyadic conversations with AI Agents.

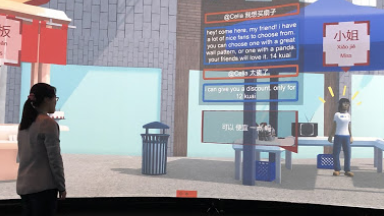

A specific use case for it is demonstrated by the Chinese street market simulation where multiple vendors compete with each other to get the business of a buyer. In our scenario, a student acts as a buyer while two AI agents allow the student to haggle over items and also try to one-up each other in an attempt to sell their goods, thus exposing them to group conversations as well as the cultural nuances of street markets in China.

The multi-modal multi-agent system opens up new research opportunities of mutli-lateral negotiations between AI agents and humans. The research opportunities were presented to the research community at large in the form of an international AI competition called HUMAINE: Human Multi-Agent Immersive Negotiation Competition at Automated Negotiating Agents Competition (ANAC) at the International Joint Conference of AI (IJCAI) 2020.

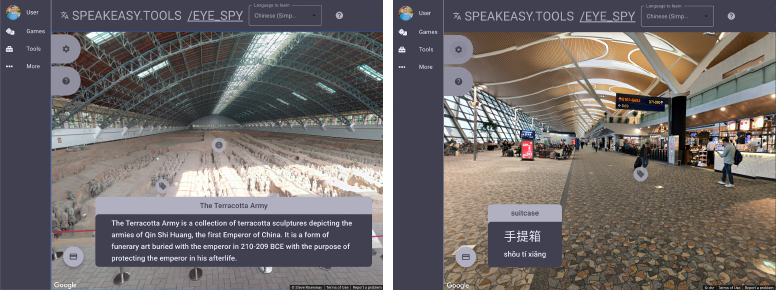

Panoramic scenes

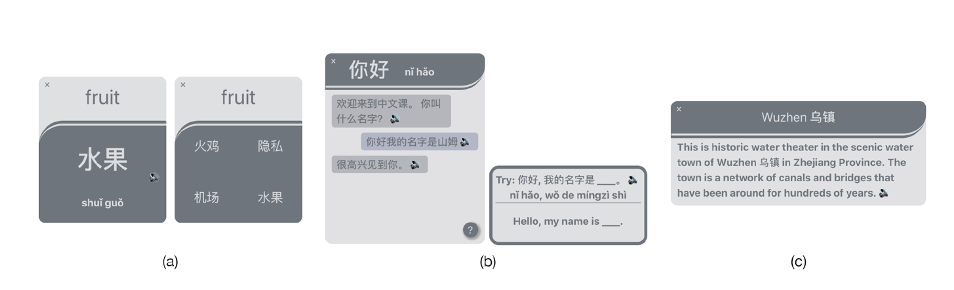

Panoramic Scene technologies utilizes real-world 360° images to create authentic experiences for students to explore vocabulary and cultural knowledge. The use of true-to-life locations immerses students in real-world settings to learn and practice foreign languages.

Cultural Knowledge

Interactive information cards embedded in a scene bring cultural knowledge to attention through relevant text about what users may be experiencing. Gesture controls capture hand motions: pointing with a hand and closing into a fist clicks on items in the scene allowing interactions without intrusive devices used commonly in motion tracking. When information cards are clicked on, target words and phrases are read aloud for pronunciation understanding.

Vocabulary Learning

Students can learn and practice target words through an exploration of actual items and objects within the scene in the word’s context. These interactive items engage the student in two modes that can be toggled between Explore and Practice. In Explore mode, the student opens flashcards featuring the target word’s translation in Hanzi and pronunciation in Pinyin. Practice mode transforms this flashcard into a multiple-choice quiz with four candidate translations. Selecting an answer reads it aloud and reveals its English translation.

Sentence-level Practice

Students engage with dialogue cards to practice listening comprehension and speaking. Opening a card reveals a dialog box that prompts the student aloud with a statement or question related to content in the scene. Students can speak their response; what is heard by the system shows on the screen as a text transcript so students can see where they may have difficulty with pronunciation. Those struggling to answer the prompt can access assistance by toggling a tray of candidate responses. The system can play the audio for these aloud so users may “listen and repeat”.

SpeakEasy

SpeakEasy is a browser based application composed of different games, puzzles, and interactive experiences. Students can play the games 2048, memory, and I-Spy using a foreign language. One of the most notable applications in SpeakEasy is the tone trainer. Native speaker examples are provided to students through audio samples, fundamental frequency visualizations, and grapheme and phoneme level timelines. A student can practice their pronunciation and receive real time feedback on the accuracy of their tones in comparison to a native speaker.

The tonal trainer can be utilized in the ILLE.

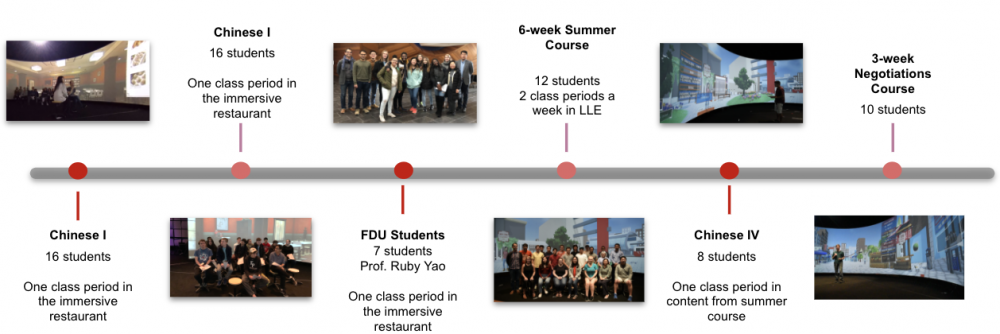

Findings

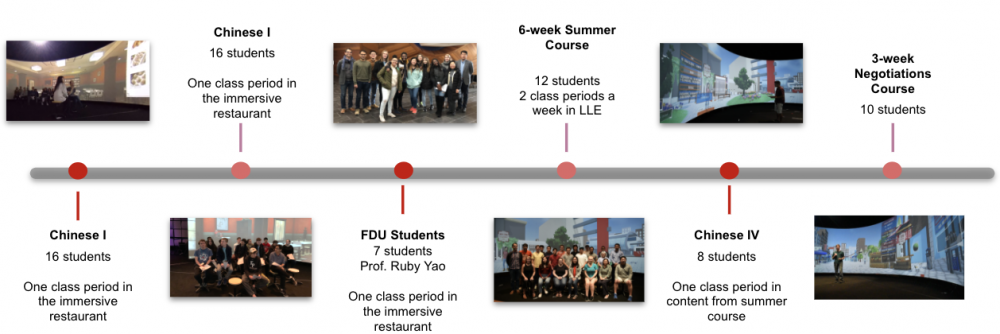

Throughout 2017-2020, multiple user studies were conducted with the ILLE to evaluate the environment. The first three evaluations focused solely on a dining experience in an immersive Chinese restaurant. Classes of beginner Chinese students (2 from RPI, 1 from FDU) visited the ILLE after learning a unit on food in their class. Student feedback from the first three evaluations indicated a high likeability. Students found the dialogues realistic and the immersive environment useful for Chinese as a foreign language (CFL) learning. Students liked being able to gesture to an item on the menu when they were unsure of how to order.

The students also found the interactive nature of game-like restaurant activities to be helpful for their CFL acquisition because of how it mirrored real-life situations. Additionally, the students were provided with the option to ask the waiter for help in their conversations. Each of the groups tested found themselves using this feature of the simulation to facilitate meaningful conversation that broadened their knowledge of the intricacies of the language at hand.

AI-Assisted Immersive Chinese

The ILLE was integrated into a 6-week summer course, AI-Assisted Immersive Chinese, taught by Professor Helen Zhou at RPI. 12 undergraduate students were enrolled in the course, which met four times a week for six weeks. Two of those days were spent in the traditional classroom, and two days were spent in the ILLE. The time in the ILLE was split between Virtual World interactions and Panoramic Scene exploration.

AI-Assisted Immersive Chinese aimed to prepare students for a study abroad trip to Shanghai in China. Learning outcomes focused on survival phrases, vocabulary, and communication goals around themes such as travel, food and dining, and shopping.

At the end of the course, 11 students participated in a survey. More than half of the students (8/11) strongly agreed that they had fun in the ILLE.

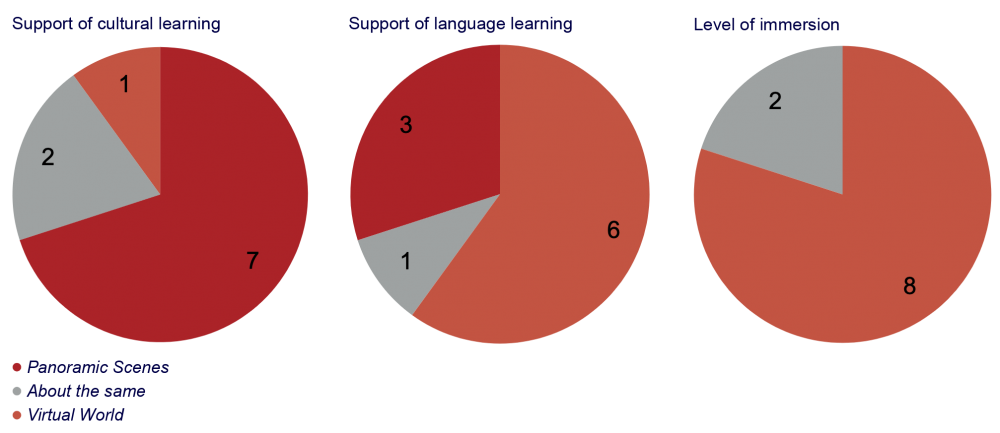

Because this was the first evaluation of the new Panoramic Scenes technology, it was important to gather specific feedback about both of these experiences. When asked to compare preferences within Panoramic Scenes and Virtual World experiences, feedback was fairly mixed. Four students preferred the Virtual World experience, four students preferred the Panoramic Scene experience, and three students felt about the same for either experience. Furthermore, students felt that the Virtual World provided a higher level of immersion, but the Panoramic Scenes provided better support of cultural learning. Regarding which environment provided better support for language learning, six students selected Virtual World, three students selected Panoramic Scenes, and two students selected they were about the same.

This suggests that, moving forward, a combination of Virtual World and Panoramic Scene elements should be available for learners in the ILLE.

The technology supporting the ILLE is always evolving, and new technologies and features were integrated into the ILLE between evaluations. Notably, for the 6-week summer course, the ILLE experience included Panoramic Scenes and more Virtual World experiences. One of these Virtual World experiences included a multi-agent conversation in which a student could have a conversation with two agents selling goods on a street market in China. These agents negotiated prices with the student, occasionally butting into the conversation to offer competing prices.

An initial, informal evaluation of this technology included a higher level Chinese class from RPI coming to the ILLE to practice their negotiation skills with the agents. Through observations, the team was able to note student successes, as well as challenging interactions that needed refinement before formal testing.

An analysis of the course AI-Assisted Immersive Chinese was published and presented at HCI International ‘19, the 6th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network, and IBM AI Research Week 2019.

Formal Negotiations Study

This work was published in the Computer Assisted Language Learning Journal as Foreign language acquisition via artificial intelligence and extended reality: design and evaluation.

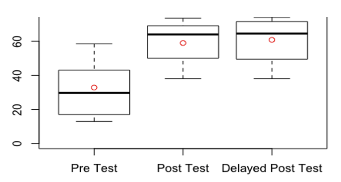

In the spring of 2020, a formal 3-week user study with 10 participants (N=10) was conducted to determine if the ILLE is an effective tool for CFL. The goal of the study was to measure if specific CFL knowledge could be learned by students in the ILLE. The learning content for the study included 32 vocabulary words and 6 sentence structures related to shopping for fruits at markets in China.

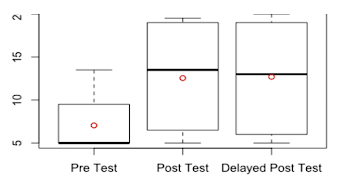

Effectiveness was measured quantitatively through listening, comprehension, translation, and conversational proficiency scores tracked across each participant’s pre-, post-, and delayed post-tests, as well as through students’ self-reported learning gains. Qualitative measurements were provided by data gathered from a questionnaire distributed after the study.

Overall the ILLE proved to be an effective tool for learning Mandarin Chinese. Students’ proficiency across vocabulary, listening, comprehension, and conversation increased significantly between the pre- and post-tests. There was no significant change between the post- and delay-post-test scores, indicating knowledge and proficiency were retained.

Nine out of ten students indicated learning new cultural knowledge, and many noted cultural differences they had learned in their questionnaire responses; for example, “In the US, we use coupons instead of asking for discounts.” Participants also indicated that they felt more prepared and confident to negotiate in Chinese after their learning experience.

Participants noted the Virtual World as useful for improving conversation and proficiency skills, and the Panoramic Scenes as helpful for enforcing vocabulary. A majority of the students (7/10) answered that they were less anxious talking to the AI avatars compared to humans.

One student remarked, “...my main takeaway from Panoramic Scenes was the vocabulary in context. The way it had me interacting with the new material built a good foundational association between the words and what they meant.” Other students said of the Virtual World, “I got to see what it was like to barter [negotiate] for the first time,” “I learned... basic conversations that we would have with vendors or store owners when trying to buy goods,” and “..it helped me become more comfortable recognizing phrases and understanding new content in a spoken conversation.”

Faculty

Affiliated Faculty

Research Staff

Students

Publications

2021

- . "Foreign language acquisition via artificial intelligence and extended reality: design and evaluation," Computer Assisted Language Learning (2021): pp. 1-29. [Publication, Abstract]

2020

- . "A collaborative, immersive language learning environment using augmented panoramic imagery," 2020 6th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network (iLRN), 2020, pp. 225–229. [Publication, Abstract]

- . "SpeakEasy: Browser-based automated multi-language intonation training. (A)," The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 148, no. 4 (2020): 2697. [Publication, Abstract]

2019

- . "The Rensselaer Mandarin Project — A Cognitive and Immersive Language Learning Environment," Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence - Demonstration Track, vol. 33, pp. 9845-9846. 2019. [Publication, Abstract]

- . "Automated Mandarin tone classification using deep neural networks trained on a large speech dataset," The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 145, no. 3 (2019): 1814-1814. [Publication, Abstract]

- . "Embodied Conversational AI Agents in a Multi-modal Multi-agent Competitive Dialogue," Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence Demos. Pages 6512-6514 [Publication, Abstract]

- . "Building Human-Scale Intelligent Immersive Spaces for Foreign Language Learning," Proceedings of iLRN 2018 Montana (2018): 94. [Publication, Abstract]

- . "Language Learning in a Cognitive and Immersive Environment Using Contextualized Panoramic Imagery," In: Stephanidis C. (eds) HCI International 2019 - Posters. HCII 2019. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1034. Springer, Cham [Publication, Abstract]

2018

- Divekar, Rahul R., Jaimie Drozdal, Yalun Zhou, Ziyi Song, David Allen, Robert Rouhani, Rui Zhao, Shuyue Zheng, Lilit Balagyozyan, and Hui Su.. "Interaction Challenges in AI Equipped Environments Built to Teach Foreign Languages Through Dialogue and Task-Completion.," In Proceedings of the 2018 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2018, pp. 597-609. ACM, 2018. [Publication, Abstract]

- Divekar, Rahul R., Yalun Zhou, David Allen, Jaimie Drozdal, and Hui Su. "Building Human-Scale Intelligent Immersive Spaces for Foreign Language Learning," [Publication, Abstract]

Videos

Additional Videos

Articles

- Creative Connections, Transformative Innovations (2016)

- Encouraging Creative Connections: How four National Medal Laureates found inspiration - and hope to spark creativity in others (2016)

- Rensselaer Re-Establishing Chinese Language Minor (2014)

- Beijing in North Greenbush (2014)

- "The Mandarin Project," Virtual Reality Immersive Language Course Featured in Times of London (2014)

- Studying Chinese in Beijing, by way of Rensselaer (2013)

- Code Name – “The Mandarin Project” (2012)